UPDATE 2017-04-03: Unicode strings are used when needed. See the update post.

You can uncover an artifact from the deepest and darkest depths of an operating system and build a tool to rip it apart for analysis, but if everybody stares at it with a confused look on their faces it won’t gain acceptance and no one will use this new thing you did. Something about forensics, Daubert, Frye, etc., not to mention plain reasoning.

With that said, this post is a followup to my previous post about the Python and EnScript carving tools that can be used to analyze data from the WMI repository database, and more specifically, the class CCM_RecentlyUsedApps that is contained within. That post was about the structure of the records, and how to locate and then parse the meaningful data into property lists. This post is about what these properties mean and how they can be used.

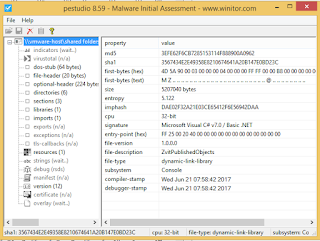

Header Data

The indexing of the WMI repository uses hashes to better store and locate the various namespaces and classes in the file. These hashes are placed at the beginning of each of these records. The way the hashes are calculated are discussed in the previous post.

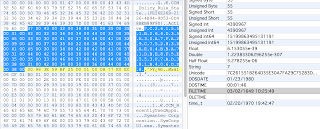

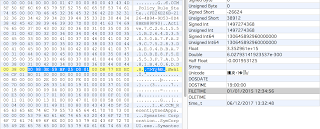

There are two date properties that are part of the record header, in the Microsoft FileTime format that occupies 8 bytes each. Both of these dates are stored in UTC. With these dates being part of the record header, they will be found on records in all types of classes, not just those being used with the CCM_RecentlyUsedApps tracking.

Timestamp1 indicates the last date the system had some sort of checkin or assessment from the SCCM server. It will be the same for all actively allocated records. You will very likely find previous dates on some records when using the carving method since there are records that get deallocated but not overwritten. The systems that I have analyzed these artifacts from have all had roughly a week between the various dates. I suspect this is a configuration setting that an SCCM admin would be able to modify.

Timestamp2 seems to indicate when the system was last initiated to join SCCM. This will be the same for all records, even with the carving method. The only reason this date would change on some records, was if the system was removed from being managed by SCCM and then joined again. This date has always lined up well, in my research and investigations, with other artifacts that support an action of joining an SCCM management group, such as services being created or drivers installed.

Numeric Record Data

There are 3 numeric properties stored in the record data: Filesize, ProductLanguage, and LaunchCount. None of these are going to sound any alarms on their own, but they can help paint the picture when combined with the rest of the properties.

Filesize is a four byte field that tracks the bytes of the executable for the record. Depending on if the developer used a signed type or unsigned, four bytes has a max value of 4GiB (unsigned) or 2GiB (signed). If you have a bunch of Adobe products on your systems, you might run into these size limitations, but every other program should be just fine for now. This field is end capped by other properties/offsets on both sides, so it’s not a question of reverse engineering (guessing) as how big it is. It is four bytes.

ProductLanguage is a four byte field that holds an integer related to the language designed by the developer. This sounds like a good possibility for filtering, but I have found tons of legitimate programs that have 0 for this field. I regularly see both 0 and 1033 on the systems I have analyzed.

LaunchCount is a four byte field that holds an integer representing the number of times this executable has been run on this system. I have seen programs with five digit decimal numbers on some systems! This won’t be common because one of the string fields tracked is the version of the binary. New version number, completely new record. Unlike Windows Prefetch, you won’t find a ton of articles written by idiots telling the world to delete all data associated with CCM_RecentlyUsedApps. Give it a couple months.

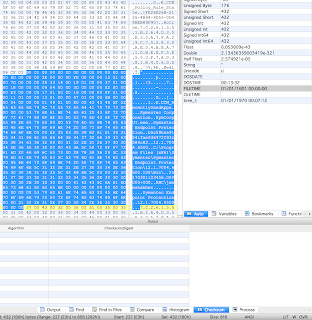

String Record Data

I don’t want to list out every one of the string properties here since many of them are really quite self-explanatory. I want to touch on a few that would either be very helpful or have some caveats that go with them. If any one of these properties were to change value for a binary, there will be a whole new record created for the new data.

ExplorerFilename is the name of the binary as it is seen by the filesystem. If this name changes, there will be a new record as stated above.

OriginalFilename is one of many strings that come from the properties contained in the binary data, usually towards the end of the file. You might think that comparing this field to the ExplorerFilename would be a good way of filtering your data down to those suspicious binaries, and I would applaud you for the thought process of getting there (that is getting into the threat hunting mindset). The reality is that there are a ton of legitimate programs distributed through legitimate channels that were compiled into a different filename than how it was packaged up before sending to you. (Slack, I am looking at you) It is one method of trying to digest this data that can lead to good findings, but it isn’t going to do your job for you. Many of the native Windows binaries have a ‘.mui’ appended after the ‘.exe’ in this field, just to throw us all off a bit.

LastUsedTime is a date time value stored as a string. The format is yyyyMMddHHmmss.000000+000, and I have not seen any timezones applied on any of the systems I have analyzed. There is a caveat with this property. The time recorded is the last time the program was running. Effectively, it is the last time the program was shutdown. I have confirmed this many times by multiple sources. One source is the log file created from our automated collection script, and I am able to lineup this timestamp with the end of the tool every time.

FilePropertiesHash is a great property when it exists. I haven’t been able to determine why, but some systems have a value filled in while others don’t. It is consistent within an environment in that all systems from a given customer either have it or don’t have it. The hash is in SHA1, and it is a hash of the binary data.

SoftwarePropertiesHash is a hash of something, but it is not the binary data. Also, it isn’t always there, though it tends to show up if the ‘msi’ prefix fields have values. I have had many records that have the FilePropertiesHash, but the SoftwarePropertiesHash is empty.

FolderPath has been an accurate property telling where the binary existed when it was executed. If the binary is moved, this record will become stale as a new one is created with the new path.

LastUserName tracks what appears to be the user account that was used to execute. I would still like to validate this a bit further, however. Every record that I have identified as critical to a case has been backed up by other artifacts showing this username executed the file. It may be the last user to have authenticated on the system before this executable was run, but I have not run into that scenario in order to dis/prove. Please let me know if you find this means otherwise.

Analysis Considerations

A few of my thoughts about analyzing this data. Please share your own.

Blanks

Many of the properties come from the section of the executable that stores properties about the program: CompanyName, FileDescription, FileVersion, etc. You might think that malware authors are lazy and leave these fields empty because they serve no purpose, and you would be correct part of the time. Looking for blanks can be one method, but it is not a guarantee. A few points:

Don’t assume all malware authors are lazy

Some malware these fields filled with legitimate looking data – #opsec

Remember that many attackers use the ‘Live off the land’ method of using what exists on the system

Many legitimate programs will leave these fields empty

Some legitimate programs I have run across in my analysis of this CCM_RecentlyUsedApps data that have blank fields are pretty surprising. These programs have been in categories across the board. I thought about providing a list of these executable names, but some are a bit sensitive. Instead, here is a list of some categorically.

Python binaries

Anti-virus main and secondary tools

Point Of Sale main and updater programs

Tons of DFIR tools

Java

Google Chrome secondary tools

Driver installers

On the opposite side, I have seen some advanced malware use these properties very strategically. There was one that even properly used the FileVersion field. I found records from different systems and places that showed 3 incriminating versions that were active on the network.

Name or Path

I noted this above, but keep in mind if after running an executable at least once that even a single character changes for either the name or path, the previous record is alienated and a new one is created. With the assumption that no data and only the name or path changed, the FilePropertiesHash can be used to find identical binaries.

Large Scale Aggregated Data

I designed the EnScript to be run against any number of systems and output the results to a single file. This gives the investigator the ability to perform analysis against the data in aggregation. Importing this data into a relational database (MSSQL, MySQL, SQLite, etc) gives a huge advantage when analyzing this data at scale. Outliers can be quickly identified through a number of different techniques.

For example, a simple ‘group by’ query that counts the number of systems that each executable has been run on can really jump start the findings.

Select distinct ExplorerFilename, FolderPath, count(EvFilename) as SystemCount

From tablename

group by ExplorerFilename, FolderPath

order by SystemCount

Excel pivot tables can provide similar analysis, though not quite as flexible.

I hope this is able to help some of you track things down a bit faster. We as an industry can use any help we can get to reduce the time between detection and remediation.

James Habben

@JamesHabben Continue reading CCM_RecentlyUsedApps Properties & Forensics→