Posted by Megan Ruthven Android Security, Ken Bodzak Threat Analysis Group, Neel Mehta Threat Analysis Group

Android Security is always developing new ways of using data to find and block potentially harmful apps (PHAs) from getting onto your devices. Earlier this year, we announced we had blocked Chrysaor targeted spyware, believed to be written by NSO Group, a cyber arms company. In the course of our Chrysaor investigation, we used similar techniques to discover a new and unrelated family of spyware called Lipizzan. Lipizzan’s code contains references to a cyber arms company, Equus Technologies.

Lipizzan is a multi-stage spyware product capable of monitoring and exfiltrating a user’s email, SMS messages, location, voice calls, and media. We have found 20 Lipizzan apps distributed in a targeted fashion to fewer than 100 devices in total and have blocked the developers and apps from the Android ecosystem. Google Play Protect has notified all affected devices and removed the Lipizzan apps.

We’ve enhanced Google Play Protect’s capabilities to detect the targeted spyware used here and will continue to use this framework to block more targeted spyware. To learn more about the methods Google uses to find targeted mobile spyware like Chrysaor and Lipizzan, attend our BlackHat talk, Fighting Targeted Malware in the Mobile Ecosystem.

How does Lipizzan work?

Getting on a target device

Lipizzan was a sophisticated two stage spyware tool. The first stage found by Google Play Protect was distributed through several channels, including Google Play, and typically impersonated an innocuous-sounding app such as a “Backup” or “Cleaner” app. Upon installation, Lipizzan would download and load a second “license verification” stage, which would survey the infected device and validate certain abort criteria. If given the all-clear, the second stage would then root the device with known exploits and begin to exfiltrate device data to a Command & Control server.

Once implanted on a target device

The Lipizzan second stage was capable of performing and exfiltrating the results of the following tasks:

- Call recording

- VOIP recording

- Recording from the device microphone

- Location monitoring

- Taking screenshots

- Taking photos with the device camera(s)

- Fetching device information and files

- Fetching user information (contacts, call logs, SMS, application-specific data)

The PHA had specific routines to retrieve data from each of the following apps:

- Gmail

- Hangouts

- KakaoTalk

- LinkedIn

- Messenger

- Skype

- Snapchat

- StockEmail

- Telegram

- Threema

- Viber

- Whatsapp

We saw all of this behavior on a standalone stage 2 app, com.android.mediaserver (not related to Android MediaServer). This app shared a signing certificate with one of the stage 1 applications, com.app.instantbackup, indicating the same author wrote the two. We could use the following code snippet from the 2nd stage (com.android.mediaserver) to draw ties to the stage 1 applications.

Morphing first stage

After we blocked the first set of apps on Google Play, new apps were uploaded with a similar format but had a couple of differences.

The apps changed from ‘backup’ apps to looking like a “cleaner”, “notepad”, “sound recorder”, and “alarm manager” app. The new apps were uploaded within a week of the takedown, showing that the authors have a method of easily changing the branding of the implant apps.

The app changed from downloading an unencrypted stage 2 to including stage 2 as an encrypted blob. The new stage 1 would only decrypt and load the 2nd stage if it received an intent with an AES key and IV.

Despite changing the type of app and the method to download stage 2, we were able to catch the new implant apps soon after upload.

How many devices were affected?

There were fewer than 100 devices that checked into Google Play Protect with the apps listed below. That means the family affected only 0.000007% of Android devices. Since we identified Lipizzan, Google Play Protect removed Lipizzan from affected devices and actively blocks installs on new devices.

What can you do to protect yourself?

- Ensure you are opted into Google Play Protect.

- Exclusively use the Google Play store. The chance you will install a PHA is much lower on Google Play than using other install mechanisms.

- Keep “unknown sources” disabled while not using it.

- Keep your phone patched to the latest Android security update.

List of samples

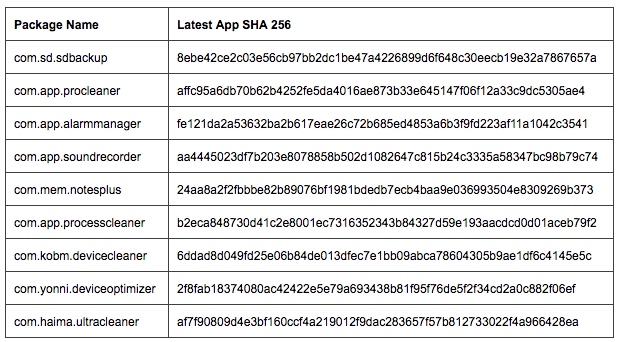

1st stage

Newer version

Standalone 2nd stage

Continue reading From Chrysaor to Lipizzan: Blocking a new targeted spyware family→

Continue reading From Chrysaor to Lipizzan: Blocking a new targeted spyware family→