toolsmith #114: WireEdit and Deep Packet Modification

PCAPs or it didn’t happen, right?

Introduction

Packet heads, this toolsmith is for you. Social media to the rescue. Packet Watcher (jinq102030) Tweeted using the #toolsmith hashtag to say that WireEdit would make a great toolsmith topic. Right you are, sir! Thank you. Many consider Wireshark the eponymous tool for packet analysis; it was only my second toolsmith topic almost ten years ago in November 2006. I wouldn’t dream of conducting network forensic analysis without NetworkMiner (August 2008) or CapLoader (October 2015). Then there’s Xplico, Security Onion, NST, Hex, the list goes on and on…

Time to add a new one. Ever want to more easily edit those packets? Me too. Enter WireEdit, a comparatively new player in the space. Michael Sukhar (@wirefloss) wrote and maintains WireEdit, the first universal WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) packet editor. Michael identifies WireEdit as a huge productivity booster for anybody working with network packets, in a manner similar to other industry groundbreaking WYSIWIG tools.

In Michael’s own words: “Network packets are complex data structures built and manipulated by applying complex but, in most cases, well known rules. Manipulating packets with C/C++, or even Python, requires programming skills not everyone possesses and often lots of time, even if one has to change a single bit value. The other existing packet editors support editing of low stack layers like IPv4, TCP/UDP, etc, because the offsets of specific fields from the beginning of the packet are either fixed or easily calculated. The application stack layers supported by those pre-WireEdit tools are usually the text based ones, like SIP, HTTP, etc. This is because no magic is required to edit text. WireEdit’s main innovation is that it allows editing binary encoded application layers in a WYSIWYG mode.“

I’ve typically needed to edit packets to anonymize or reduce captures, but why else would one want to edit packets?

1) Sanitization: Often, PCAPs contain sensitive data. To date, there has been no easy mechanism to “sanitize” a PCAP, which, in turn, makes traces hard to share.

2) Security testing: Engineers often want to vary or manipulate packets to see how the network stack reacts to it. To date, that task is often accomplished via programmatic means.

WireEdit allows you to do so in just a few clicks.

Michael describes a demo video he published in April 2015, where he edits the application layer of the SS7 stack (GSM MAP packets). GSM MAP is the protocol responsible for much of the application logic in “classic” mobile networks, and is still widely deployed. The packet he edits carries an SMS text message, and the layer he edits is way up the stack and binary encoded. Michael describes the message displayed as a text, but notes that if looking at the binary of the packet, you wouldn’t find it there due to complex encoding. If you choose to decode in order to edit the text, your only option is to look up the offset of the appropriate bytes in Wireshark or a similar tool, and try to edit the bytes directly.

This often completely breaks the packet and Michael proudly points out that he’s not aware of any tool allowing to such editing in WYSIWYG mode. Nor am I, and I enjoyed putting WireEdit through a quick validation of my own.

Test Plan

I conceived a test plan to modify a PCAP of normal web browsing traffic with web application attacks written in to the capture with WireEdit. Before editing the capture, I’d run it through a test harness to validate that no rules were triggered resulting in any alerts, thus indicating that the capture was clean. The test harness was a Snort 2.9.8.0 instance I’d implemented on a new Ubuntu 14.04 LTS, configured with Snort VRT and Emerging Threats emerging-web_server and emerging-web_specific_apps rules enabled. To keep our analysis all in the family I took a capture while properly browsing the OpenBSD entry for tcpdump.

A known good request for such a query would, in text, as a URL, look like:

http://www.openbsd.org/cgi-bin/man.cgi/OpenBSD-current/man8/tcpdump.8?query=tcpdump&sec=8

Conversely, if I were to pass a cross-site scripting attack (I did not, you do not) via this same URL and one of the available parameters, in text, it might look something like:

http://www.openbsd.org/cgi-bin/man.cgi/OpenBSD-current/man8/tcpdump.8?query=tcpdump&sec=8%22onmouseover%3Dalert(1337)%2F%2F

Again though, my test plan was one where I wasn’t conducting any actual attacks against any website, and instead used WireEdit to “maliciously” modify the packet capture from a normal browsing session. I would then parsed it with Snort to validate that the related web application security rules fired correctly.

This in turn would validate WireEdit’s capabilities as a WYSIWYG PCAP editor as you’ll see in the walk-though. Such a testing scenario is a very real method for testing the efficacy of your IDS for web application attack detection, assuming it utilized a Snort-based rule set.

Testing

On my Ubuntu Snort server VM I ran sudo tcpdump -i eth0 -w toolsmith.pcap while browsing http://www.openbsd.org/cgi-bin/man.cgi/OpenBSD-current/man8/tcpdump.8?query=tcpdump&sec=8.

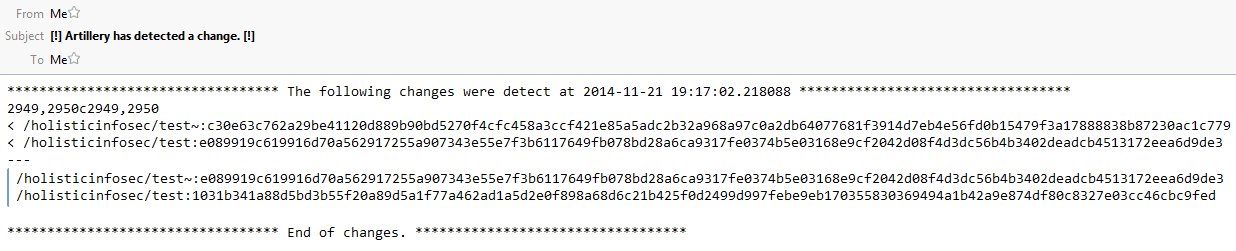

Next, I ran sudo snort -c /etc/snort/snort.conf -r toolsmith.pcap against the clean, unmodified PCAP to validate that no alerts were received, results noted in Figure 1.

|

| Figure 1: No alerts triggered via initial OpenBSD browsing PCAP |

I then dragged the capture (407 packets) over to my Windows host running WireEdit.

Now wait for it, because this is a lot to grasp in short period of time regarding using WireEdit.

In the WireEdit UI, click the Open icon, then select the PCAP you wish to edit, and…that’s it, you’re ready to edit. 🙂 WireEdit tagged packet #9 with the pre-requisite GET request marker I was interest in so expanded that packet, and drilled down to the HTTP: GET descriptor and the Request-URI under Request-Line. More massive complexity, here take notes because it’s gonna be rough. I right-clicked the Request-URI, selected Edit PDU, and edited the PDU with a cross-site scripting (JavaScript) payload (URL encoded) as part of the GET request. I told you, really difficult right? Figure 2 shows just how easy it really is.

|

| Figure 2: Using WireEdit to modify Request-URI with XSS payload |

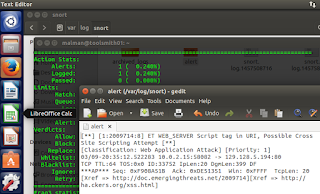

I then saved the edited PCAP as toolsmithXSS.pcap and dragged it back over to my Snort server and re-ran it through Snort. The once clean, pristine PCAP elicited an entirely different response from Snort this time. Figure 3 tells no lies.

|

| Figure 3: XSS ET Snort alert fires |

Perfect, in what was literally a :30 second edit with WireEdit, I validated that my ten minute Snort setup catches cross-site scripting attempts with at least one rule. And no websites were actually harmed in the making of this test scenario, just a quick tweak with WireEdit.

That was fun, let’s do it again, this time with a SQL injection payload. Continuing with toolsmithXSS.pcap I jumped to the GET request in frame 203 as it included a request for a different query and again edited the Request-URI with an attack specific for MySQL as seen in Figure 4.

I saved this PCAP modification as toolsmithXSS_SQLi.pcap and returned to the Snort server for yet another happy trip Snort Rule Lane. As Figure 5 represents, we had an even better result this time.

|

| Figure 5: WireEdited PCAP trigger multiple SQL injection alerts |

In addition to the initial XSS alert firing again, this time we collected four alerts for:

- ET WEB_SERVER MYSQL SELECT CONCAT SQL Injection Attempt

- ET WEB_SERVER SELECT USER SQL Injection Attempt in URI

- ET WEB_SERVER Possible SQL Injection Attempt UNION SELECT

- ET WEB_SERVER Possible SQL Injection Attempt SELECT FROM

That’s a big fat “hell, yes” for WireEdit.

Still with me that I never actually executed these attacks? I just edited the PCAP with WireEdit and fed it back to the Snort beast. Imagine a PCAP like being optimized for the OWASP Top 10 and being added to your security test library, and you didn’t need to conduct any actual web application attacks. Thanks WireEdit!

Conclusion

WireEdit is beautifully documented, with a great Quickstart. Peruse the WireEdit website and FAQ, and watch the available videos. The next time you need to edit packets, you’ll be well armed and ready to do so with WireEdit, and you won’t be pulling your hair out trying to accomplish it quickly, effectively, and correctly. WireEdit my a huge leap from not known to me to the top five on my favorite tools list. WireEdit is everything it is claimed to be. Outstanding.

Ping me via email or Twitter if you have questions: russ at holisticinfosec dot org or @holisticinfosec.

ACK

Thanks to Michael Sukhar for WireEdit and Packet Watcher for the great suggestion. Continue reading toolsmith #114: WireEdit and Deep Packet Modification